You can think of the ISM as a single document that helps Australian businesses and government know how to address cybersecurity challenges. In reality, the ISM is really a collection of different guideline documents that focus on specific areas of IT. Some of the existing guidelines address things like system hardening, database management, network management, using cryptography, and many others. These guideline documents as an aggregate can be thought of as “the ISM” and can be used to increase an organization’s cybersecurity maturity which benefits both the organization itself, but also Australian society.

What’s in the Guidelines for Secure Development section of the Australian ISM?

In December of 2021, the ACSC released the latest version of the ISM which for the first time included a Guideline for Secure Development. This document lays out a framework for building and maintaining secure software development processes. It is a total of 21 controls and is more prescriptive than what we typically see from other frameworks like APRA.

You can find the Guidelines for Secure Development here: https://www.cyber.gov.au/acsc/view-all-content/advice/guidelines-software-development

The format for this blog post

I wanted to write this blog post to help Australian orgs know about this new compliance requirement from the ACSC. The new Guidelines for Secure Development document is split into two sections which we’ll address separately below.

Those two sections are: Application development and web development.

We’ll break both of those two sections down into their individual sub-sections and the controls that exist at each one of those stages. At the end, I talk about how you can assess and implement the controls in the ISM.

From this point on I’ll refer to the Guidelines for Secure Development as “GSD” for brevity’s sake.

Okay, let’s dig in!

Section 1: Application Development

This section of the GSD is applicable to all forms of software development including: client/server, web and mobile. So special emphasis on this section should be placed on all assessments you make using the GSD.

Within this top level section there are 6 sub-sections:

- Development environments

- Secure software design

- Software bill of materials

- Secure programming practices

- Software testing

- Vulnerability disclosure program

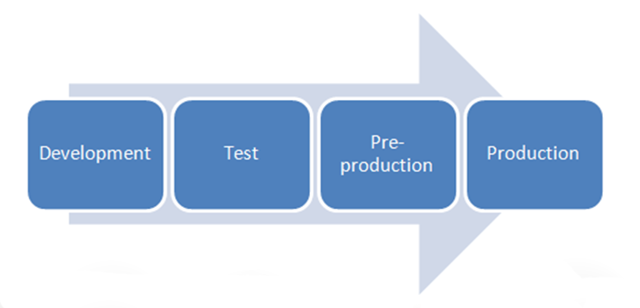

Development, Testing, and Production Environments

Segregating development, testing, pre-production and production environments into discreet separate workspaces is one of the core security principles of secure software design. This segmentation can limit accidental issues and malicious attacks from spreading from one environment to another. Software engineers are limited to dev and testing environments so that bad code or third-party issues can’t be added to production directly.

Secure Software Design and Development

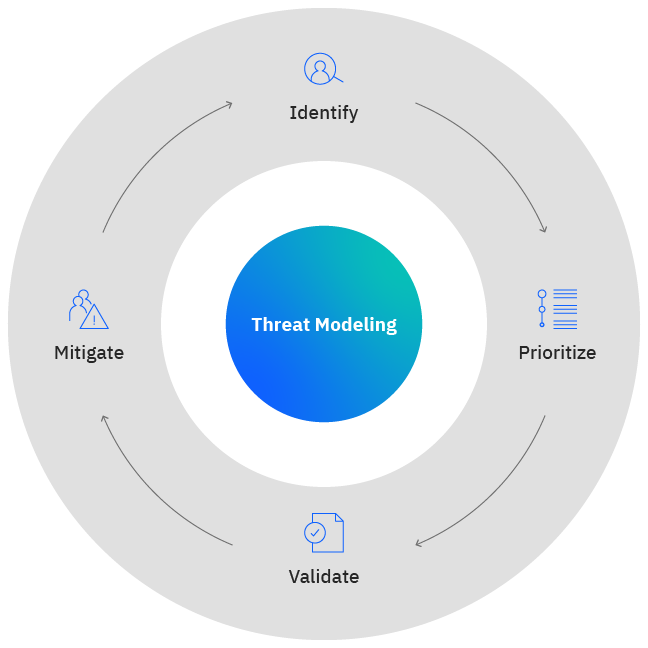

This sub-section deals with the identification of software development risk during the design and development stages. This sub-section has two controls: One for “secure design principles” and the second for threat modeling.

I feel like this section is under-baked and needs some love. What are “secure-by-design practices”? Would have loved this section to be more prescriptive. Maybe in the future, we can add things like application baselines, secure code training and application ownership labels.

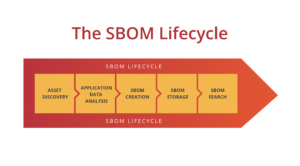

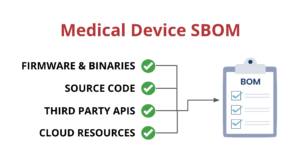

Software Bill of Materials (SBOM)

This section only has one control and it’s all about SBOM. SBOM stands for “Software Bill of Materials” and the reason that it’s so important is that it delivers something we never had had before: a complete “recipe” of what is in an application. An SBOM is a single source of truth for all software dependencies, frameworks, libraries, resources, and services that went into making a specific software solution. Most definitions of SBOM agree on the above, but some go further and say that any known vulnerabilities and cloud-based services should also be included in the SBOM. To me, this makes sense as an SBOM should be both an end-to-end description of the application, but also should list any deficiencies and liabilities. If one of the components used to build an application has a known vulnerability, it should be codified in the SBOM.

Unfortunately, SBOM hasn’t delivered on its promise yet as very few organisations are actually creating SBOMs when they build software. If you want to know more about SBOM please check out our blog post on them here: https://securestack.com/sbom/

Application testing and maintenance

There are two controls in this section. The first deals with testing software applications, both internally, as well as externally. The second talks about software engineers needing to resolve issues found in their applications. This is an important part of the document and makes no bones about the engineer’s responsibilities.

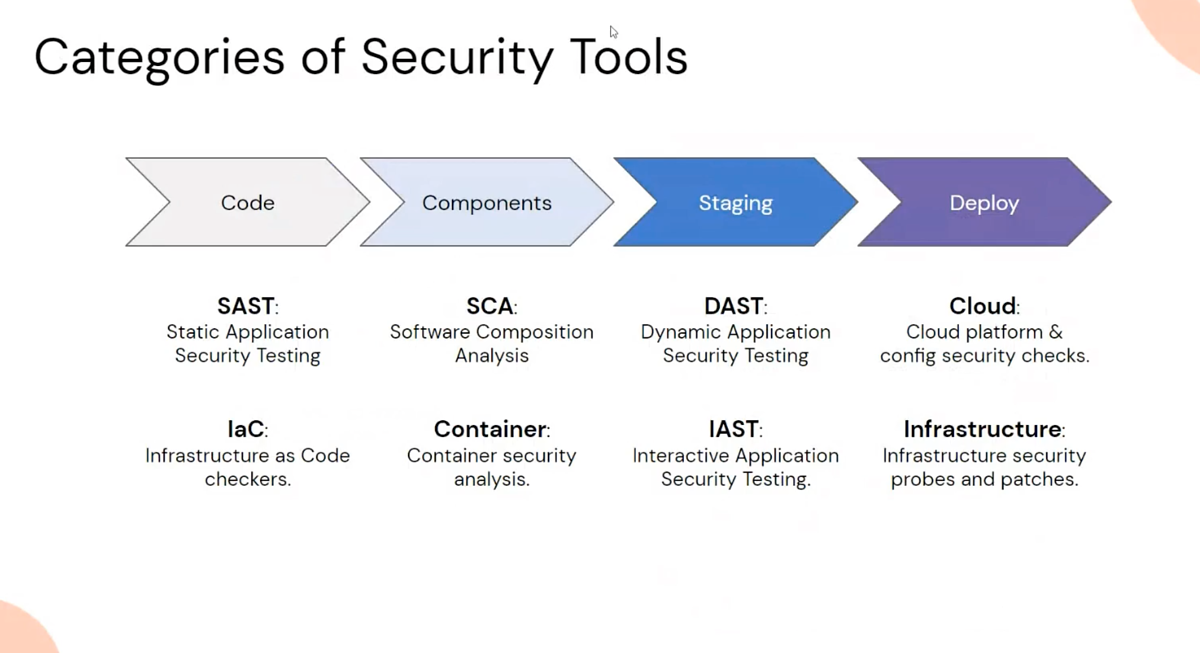

Even though there are only two controls here the description specifically calls out static analysis (SAST), dynamic analysis (DAST), web vulnerability scanning, and software composition (SCA) requirements. It also calls out penetration testing and it also mentions “prior to their initial release and following any maintenance activities”. To me, this sounds like automated tests during continuous integration and deployment (CI/CD).

So that should really be 6 controls minimum. I expect this to be fleshed out on the next version of the GSD.

Vulnerability Disclosure Program

There are actually four controls in this sub-section. The first three are somewhat redundant switching the terms “policy”, “program” and “processes” which might confuse people. Luckily the last control is straightforward and requires that orgs use a security.txt file to advertise their VDP information.

I think we can simplify this section in this way:

- Are security researchers able to come to your website and find how to contact you if they’ve found a security issue?

- Have you partnered with a platform to allow security researchers to bring security bugs they find to you?

- Do you have a set of documents that describe your security policies? And can your employees find it?

Section 2: Web Application Development

This section of the GSD is applicable to applications available on the web that users interact with primarily via a web browser. This section should be carefully following if you are building web apps.

Within this top level section there are 6 sub-sections:

-

Open Web Application Security Project

-

Web Application Frameworks

-

Web Application Interactions

-

Web Application Input Handling

-

Web Application Output Encoding

-

Web Browser-Based Security Controls

-

Web Application Event Logging

Open Web Application Security Project

The OWASP is an organization that is trying to help encourage application security through its community and projects like Zed Attack Proxy (ZAP) and the purposefully vulnerable Juice Shop project.

This section has only one control and it explicitly states that orgs should be following the Application Security Verification Standard (ASVS) when building web applications.

Web Application Frameworks

This section has one control and emphasizes the need to use existing “robust” web frameworks. I think the main point here is to use off-the-shelf components to provide session management, input handling, and cryptographic operations.

Web Application Interactions

This section has one control and it’s pretty specific: All web application content is offered exclusively using HTTPS. That sounds pretty straightforward, right?

Unfortunately, enforcing encrypted HTTP traffic is more complicated than many people think and require multiple controls and functions to be aligned. Engineers need to make sure that HTTP is redirecting to HTTPS, that HSTS is enabled and that SSL/TLS is terminated in a secure environment.

I wrote a blog post about enforcing HTTPS which you can read here: https://securestack.com/enforce-https/

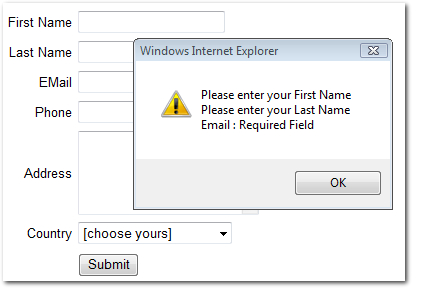

Web application input handling

This section also has one control: Validation or sanitisation is performed on all input handled by web applications. That sounds relatively straightforward but is fairly difficult to do and requires using multiple controls and functions.

Input validation requires equal parts developer training, testing of the source code, and testing the web application. That’s 3 different sets of tooling to address to achieve this requirement.

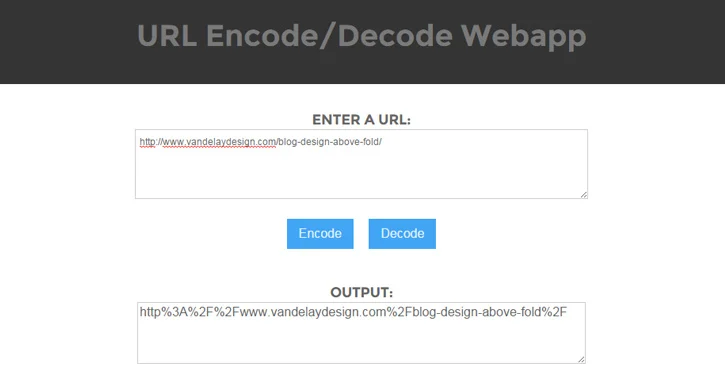

Web Application Output Encoding

This section has one control which is: Output encoding is performed on all output produced by web applications. This is a necessary requirement as the use of un-encoded data can cause serious issues as special characters can be interpreted incorrectly by the web application.

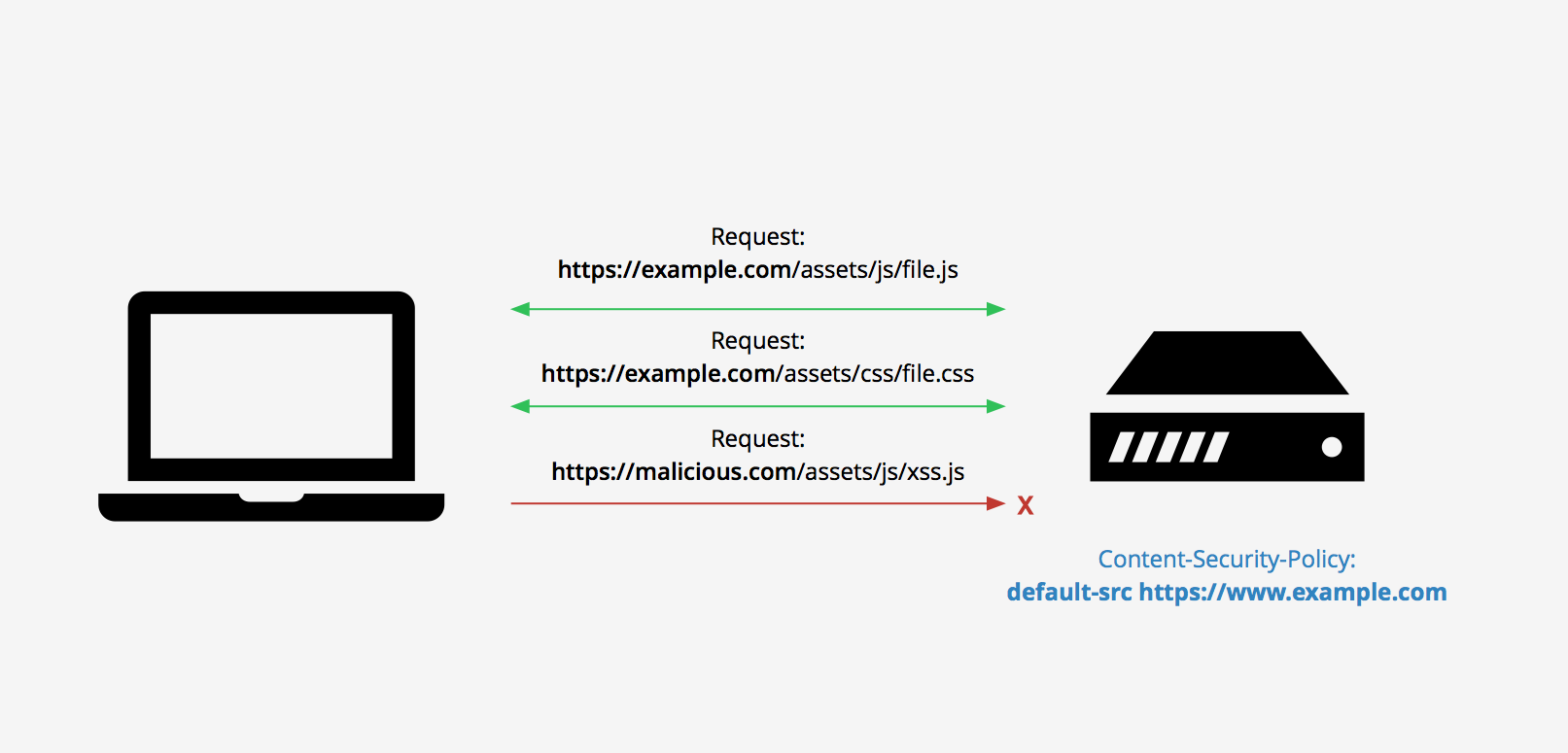

Web browser-based security controls

While this section has only one control it speaks to the need to address browser-based attacks like cross-site scripting, CSRF, and click-jacking. Modern web applications using things like Javascript run entirely in a user’s client-side browser. Traditional security controls can’t help here and this is why a new generation of controls was born, most of which are delivered as HTTP response headers. Content Security Policy, or CSP, is the best and most powerful of these but unfortunately, most websites do not use CSP.

Web application event logging

The final sub-section has two controls associated with it. The first says that all access attempts and errors need to be logged. The second, stipulates that all logs are stored centrally in another location.

Unfortunately, we see less web server and application logging than we used to. In the era of the public cloud, many engineering teams misinterpret logging functions like AWS’s Cloudwatch and Cloudtrail which log events at the cloud layer, and NOT at the application layer. To be very clear: Enabling Cloudwatch and Cloudtrail are NOT effective application logging solutions.

How do we assess and implement these controls?

Okay, so now that we’ve laid out all 16 controls in the new Guidelines for Secure Development document, where do we go from here? Well, part of the challenge of this new ISM document is that it spans across the whole software development lifecycle (SDLC). It talks about things the developer needs to do (local software testing) and it talks about segregating deployment environments. It talks about things that happen at the beginning of the lifeycycle, and things that happen at the end of the lifecycle. It talks about how to build your web applications and it talks about how your customers should be protected while using that application in a browser.

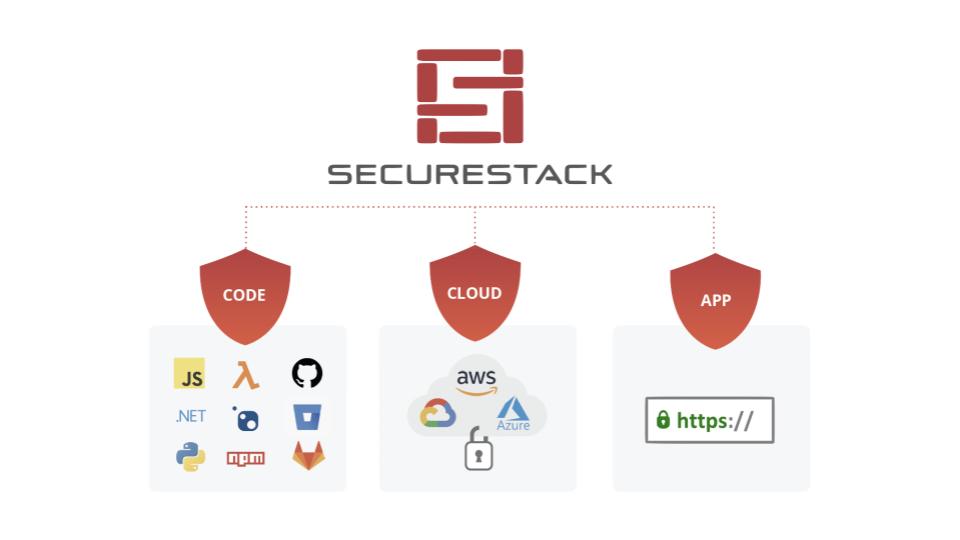

Unified ISM compliance coverage for the SDLC?

All of these disparate controls focusing on different parts of the SDLC means that there’s a broad surface area to assess and quantify against. This is one of the reasons that when we were building SecureStack we intentionally wanted to integrate into the multiple platforms our customers use. Unified coverage for the SDLC means integrating into source code management providers like GitHub, Bitbucket, and Gitlab, It also means integrating into the continuous integration and deployment and build platforms. And it definitely means integrating into the public cloud providers like AWS, Azure and GCP. But finally, it also means that you need to have continuous awareness of the web application at the heart of this as well.

How can SecureStack help you assess your ISM compliance?

The SecureStack platform can help you assess and quantify your ISM GSD compliance with our SaaS platform. We help you integrate your source code platform, CI/CD processes, build environments and your public cloud providers, and we do it all in less than 5 minutes.

Thanks right! You can see assess your entire software development lifecycle in less than 5 minutes with SecureStack. Check out the video to the left to see how!

Paul McCarty

Founder of SecureStack

DevSecOps evangelist, entrepreneur, father of 3 and snowboarder

Forbes Top 20 Cyber Startups to Watch in 2021!

Mentioned in KuppingerCole's Leadership Compass for Software Supply Chain Security!